Heat stress and health, housing for climate justice in India

Ruchika Lall | Patna and Delhi

Mubarakpur, Patna (June 2025)

We are in Mubarakpur, a periurban settlement in Patna, sitting with Aman* and his family outside their house, all of us scooting along with the shifting shadow cast by the walls in the harsh noon sun. I can feel the sweat trickle down my spine and have covered my head with my cotton dupatta. Aman has asked his wife for his own gamchaa to shelter from the heat, and offers us water. The weather app on our phones tells us it is 40 degrees Celsius today. It feels much hotter.

Garmee mein kya takleef hoti hai? I ask. The word garmee is simultaneously used for 'summer' and 'heat' in Hindi. Takleef (in Urdu) means discomfort or trouble. Depending on the tone and pacing of the question, the question itself translates in english to Do you face troubles in the summer – as well as– What troubles do you face in the summer.

As I ask the question, the absurdity of having to ask this at all, is not lost on me, or on our respondents. We are here, in one of our field sites for the If Cities Could Speak project for ethnographic fieldwork to document health histories - to understand how people across vulnerable settlements in cities in India experience, perceive and respond to climate impacts on health. I can feel anger simmering within me through the days of fieldwork in Patna and Delhi.

Nehru Nagar, Patna (June 2025)

A few days later, in another settlement in Patna, Nehru Nagar, we are sitting indoors with Sheetal*, with a wall fan on a somewhat cooler day, following an unprecedented rainy day. Sheetal almost smirks at the same question. She says… " aapke sawaal pe mujhe hansi aati hai" … " I feel like laughing at your question". She tells us, "Har Mausam ka apna andaaz hota hai….." – i.e., every season has its own personal nature, with an acceptance of not having control over the weather. She goes on to share with us in detail the many impacts of heat stress on her family's life and health.

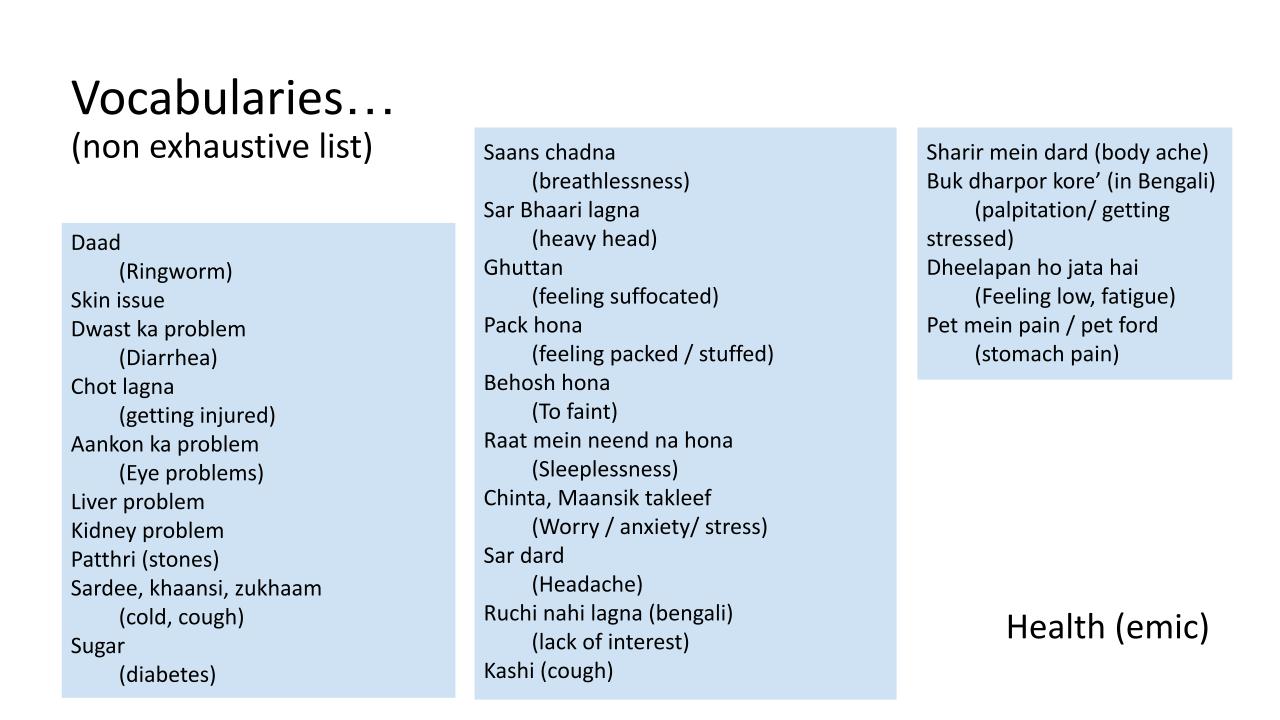

Through our fieldwork in North India in Delhi and Patna through the summer months of 2025, we repeatedly hear a range of ailments that people describe alongside heat stress (see box 1). Evident during these conversations, is how health impacts of climate change add to and intersect with pre-existing vulnerabilities that are shaped by social, spatial, economic and political exclusions for adequate and affordable housing and basic infrastructure.

Box 1: Health vocabulary from the field: excerpts from Delhi team summer fieldwork

Sheetal, for example, tells us about contamination in the water system when the pipe breaks – and how that leads to skin infections. After openly describing a case of daad or ringworm in the neighbourhood a few years ago, she clarifies to us, "I am telling you this experience of mine and this area, but if you go to the hospital, at all times you will find this for sure. These things are natural… can anyone stay alive without water?"

Sheetal connects her own and her settlement's experience to the larger city, the rules of nature and the universal need for clean water. I find myself thinking of this disclaimer from her in light of what it means to live in a vulnerable settlement – where the pipe breaks routinely, requires fixing, alongside associations of stigma attached to health and low income settlements, while there are everyday negotiations to be made for access to basic services.

We keep learning how the challenges of addressing climate impacts on health in vulnerable settlements are intersectional and layered. Climate change exacerbates poor health outcomes, in settlements with pre-existing vulnerabilities. In addition to this, the pathways to cope, respond and adapt to climate change and to access health care are also obstructed by long lasting inequalities that frame socio-economic determinants of health.

We hear similar stories in our fieldwork in Delhi too, where we have been interviewing households engaged in waste work in Bhalswa, an area that has one of the city's largest landfills. Akram*, a young waste worker shares his experience with us in detail as a door-to-door informal waste collector and recycler. When we return to meet him in the month of July, he shares with us a recent experience of harassment by the police. Such experiences shape the way he fears and hesitates to interact with the city's health care system. He shares with us how his one-year-old child has been experiencing seizures during fevers. He himself has a persistent skin rash from the heat that he is self-medicating. Similar to others whom we meet and who describe the many issues that currently add to mental stress in their lives through our conversations, he connects his experience of disenfranchisement as a bengali speaking muslim waste worker, to his and other's inability to access basic infrastructure and healthcare in the city.

Bhalswa Landfill, Delhi

"we are frogs in a well"

excerpts from field notes from interview with health practitioners, Delhi, August 2025

Bhalswa Landfill, Delhi

Half a kilometre away from Akram's house, we meet with a team of healthcare practitioners at the nearby public healthcare facility. They tell us about a range of health issues that they treat in the clinic. Even though the presence of the landfill is hard to miss in the area, they describe their practice as detached from the settlements that are adjacent to the landfill. Through our conversation, the doctors urge us to speak to another centre which has affiliations with community workers. We know however that the clinic is closed. One of the doctors tells us that they don't really know what is that side (near the landfill), they have never gone there – "hum to kuan ke maindak hai (we are frogs in a well)".

I can't help thinking how apt a phrase it is for the siloed or fragmented thinking of urban sectors that has us here globally. The frog-in-the well metaphor feels poignant alongside another popular metaphor of the slow-boiling-frog, often used to describe human reluctance to acknowledge climate change. We ask the doctors 'what can be done to improve the healthcare system', - To continue with the frog metaphors…. how do we eat the frog! What can be done that will have impact?

One of the doctors highlights how most of the ailments they treat are preventable, and ideally in today's world should not even arise. The discussion reinforces the need for housing and basic infrastructure for preventative healthcare. The doctor also says, "but if I tell someone to change their house or live elsewhere, can they really?"

As we continue with our fieldwork through the seasons, it is clear that any action for climate adaptation and health outcomes needs to at the onset address pre-existing vulnerabilities of housing. That means that in addition to a range of new ideas, to also consolidate and deepen our focus on addressing historic and multidimensional inequalities. This work requires considering the various trade-offs that communities make and their need for adequate and affordable housing. These are needs that communities have long mobilised for and advocated for themselves. As one of our interviewees in Delhi tells us - 'I have given so many years to this city…..still one hasn't had (the dignity of) one's own house… We have made this city ours, but the city has not adopted us yet".

(*note: all respondents names have been changed for anonymity)